“Night, when words fade and things come alive” – Antoine de Saint-Exupery

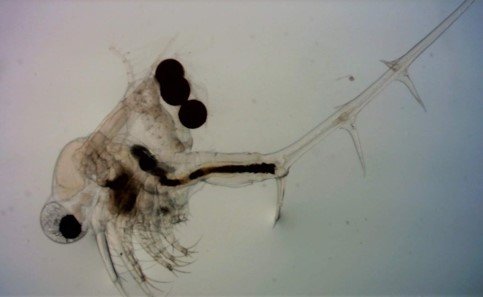

One of the species the Lower Trophic Food Webs lab is responsible for monitoring in the Great Lakes is Mysis diluviana (previously called M. relicta which is native to Northern Europe), the Opossum or Mysid Shrimp (order Peracarida, family Mysidae). For a member of the zooplankton, this species is quite large (up to 25 mm in length), and their common name comes from the females having a prominent brood pouch (a marsupium) between their thoracic legs. The body is very shrimp-like, with long antennae, stalked compound eyes, a large thoracic carapace in front of a long abdomen and a clefted telson tail. While they are concerning non-native in some inland lakes of North America, having been inappropriately introduced as “fish food”, Mysis diluviana are native to all of the Great Lakes, though they are rare in Lake Erie because it is so shallow.

Mysid shrimp are strong swimmers, but prefer deep-water habitat, generally deeper than 100 m where it is dark all day because they are strongly negatively photo-tactic (they avoid light). As such, they stay at or near the bottom of the water column during the day and some (and some don’t) migrate upwards in the water column during the night to feed on zooplankton in a strong diel vertical migration (DVM).

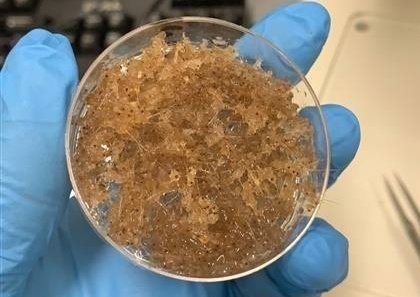

Because of this strong negative light response, along with DVM, this means that in order to sample these zooplankton, we have to do so at night, under red lights on the ship. We also have to use large nets (1 m2) so they will not swim away to avoid the nets. Lars Rudstam’s lab at Cornell University has shown that turning on the ship lights will cause the mysids to “vanish” from the sonar as they immediately start swimming downwards to avoid the light. Even a clear sky with full moon can affect capture rates so we only work from 1 hr after sunset to 1 hr before sunrise. This means that summer surveys are very limited, but is a definite advantage during the late-fall surveys when nights are much longer.

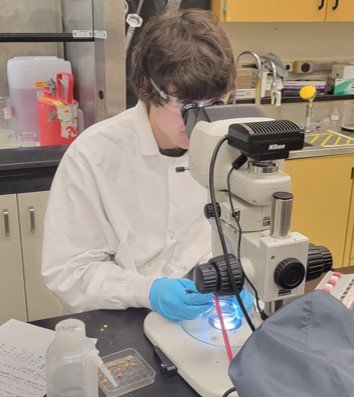

While onboard ship, we sort the mysids into gravid females, females without eggs, males and juveniles. Mysids can live for about 2 years so it is important to know what stage they are in. We generally try to pick individual gravid females directly into bullet tubes so their eggs can be retained for counts. In the lab we use microphotography to size them, and from this data, generate biomass estimates and calculate the potential population growth rates based on the gravid females. We also keep some individuals frozen for analysis of their diets using polyclonal antibodies (Berges et al. 2020) or for stable isotope or fatty-acid analysis.

Because of their large size, they are important forage for a number of fishes including Alewife, Rainbow Smelt, Cisco, and Slimy Sculpin, especially following the collapse of the large planktonic amphipod Diporeia. Since introduction of the large invasive predatory Spiny Waterflea (Bythotrephes longimanus) in the early 1980s and the Fishhook Waterflea (Cercopagis pengoi) in the 1990s, these species have also been increasingly important in the diet of forage fishes. Bythotrephes in particular, can reach its highest densities in Lake Ontario during the late-fall, so the late season survey is just as important for assessing bythos as it is for mysids.

Most of our work takes place during a late-fall (end of October or early November) Mysis and zooplankton cruise of Lake Ontario, which we have been doing since the 1970s. We didn’t get out to do our survey in 2023 because of our ship Limnos being in extended dry-dock last year, but we do try do Lake Ontario every year. We also get samples from the other Great Lakes during the spring and summer cruises, though these are much more limited in scope and depend on the ship schedule (we can only sample at night and only at deep stations). We try to do this more intensively during the Cooperative Science and Monitoring Initiative (CSMI) field-years such as Lake Huron in 2022. The EPA Great Lakes National Program Office (GLNPO) spring and summer cruises of all of the Great Lakes have provided a consistent measure of Mysis since 1997. The combined data from EPA, DFO, USGS and NOAA was used in a collaborative study with the Rudstam and Watkins labs at Cornell, to track trends of Mysis populations across the Great Lakes published just last year in the Journal of Great Lakes Research (Holda et al. 2023). This publication will be the foundation for a new Mysis sub-indicator for Habitat and Species for the State of the Great Lakes.

When we were discussing ideas for the TVO Kids Leo’s Fishheads series with the producers on related to work by DFO, I pitched the idea of going “Mysis hunting” off Toronto and it was received with enthusiasm. It required a huge amount of effort for a number of people in the lab. Kelly did the on camera hosting of the student with Dallas as Cisco Captain and host, Robin drove another boat so we could have additional shots and transporting equipment, and others were on call for various safety reasons. We had to reschedule shooting several times due to weather and other factors, and the day we had to go out wasn’t entire glass calm. The kids were troopers however. and overcame the rough conditions to finish the episode shooting. I was personally very pleased how it turned out. See the entire episode below: Counting Mysids.

Pingback: Great Lakes Food Webs Science: GLFC Lake Committees - Great Lakes Food Webs